I Know Who Killed JFK (No, Really) — It Comes Up In Executive Coaching More Than You’d Think

Strong Opinions, Weekly Held

I strongly believe I know who killed JFK.

To clarify, unfortunately, I haven’t the slightest idea if Oswald acted alone or was part of some massive conspiracy. But I’m rather certain that I know the identity of the mysterious “second shooter” who killed JFK: His name was George Hickey.

He was a Secret Service agent. It was a tragic accident.

No, I’m not joking. And yes, this astonishing fact plays a role in my executive coaching with surprising frequency.

Quick Ask: This kind of deep dive is typically reserved for paid subscribers, but I’m sharing it with everyone today! If you’re finding value in the newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber — and hey, you can probably expense it as professional development.

The Theory

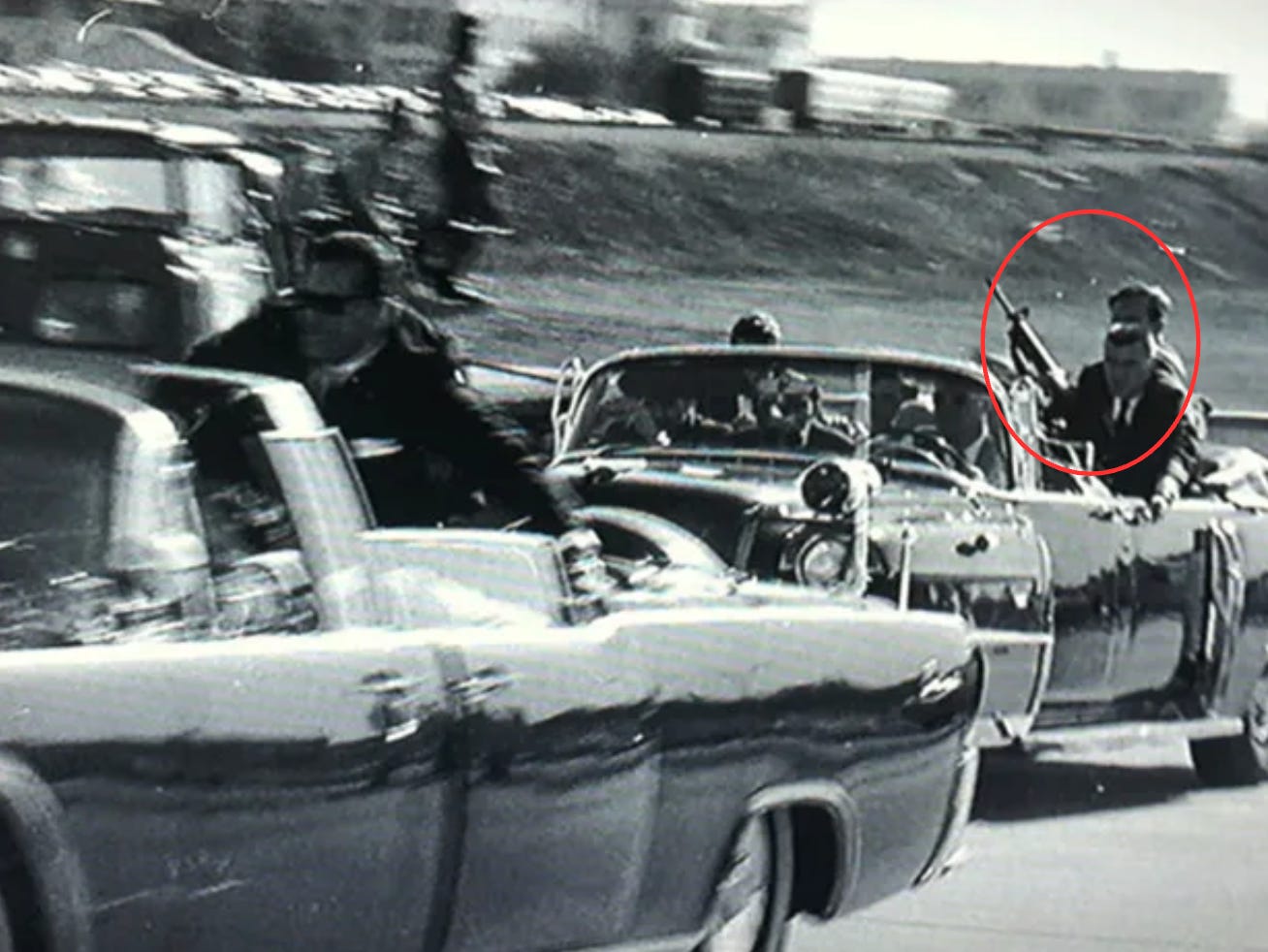

George Hickey was riding in the Secret Service convertible just behind Kennedy’s car when Oswald began shooting from the Book Depository. After hearing the first shot fired and looking around, Hickey grabbed the AR-15 rifle lying on the floor.

You can see him holding the AR-15 just moments after the shooting starts:

Then, in one of history’s most freakish and tragic accidents, Hickey fired a fatal bullet into JFK’s skull, accidentally killing the President and becoming the “second shooter”.

This theory isn’t mine, and it isn’t new.

It belongs to a ballistics expert named Howard Donahue. In 1967, Donahue was one of eleven sharpshooters invited by CBS to participate in a televised re-creation of the shooting in Dealey Plaza. Donahue then became convinced that something about the ballistics evidence was amiss and began his own decades-long investigation. After a rigorous dissection of bullet trajectories, the entry wound, and bullet fragmentations, Donahue concluded that only Hickey’s AR-15 could have fired the mysterious shot that killed JFK (although he offers that Oswald’s second shot might have irreparably wounded Kennedy anyway).

Donahue didn’t hide his findings either. His impressive ballistics deconstruction first saw daylight back in 1977 in a two-part piece for the Baltimore Sun. Most famously, his theory is captured in the comprehensive 1992 book Mortal Error: The Shot That Killed JFK by Bonar Menninger.

[Side note: That’s a first name you don’t see much anymore.]

Even stranger than the pure physics of this errant bullet perfectly striking Kennedy is that Hickey may not have even had his finger on the trigger!

Donahue believed that Hickey was standing precariously on the back seat and accidentally pressed the trigger when his car jerked forward. But there are other feasible explanations for Hickey’s misfortune. As Menninger articulated just a few years ago, these early-edition AR-15s had a common defect that caused them to prematurely fire thanks to a heavier-than-necessary firing pin. The effect was known as “slamfire”. Hickey may have simply moved the weapon and it did the rest.

What an absolutely tragic nightmare.

This Secret Service mishap theory also explains why witnesses way down on the street — far from the sixth floor Book Depository window, including a U.S. Senator — reported strong smells of gunpowder; why the government behaved so bizarrely in its handling of the body and autopsy; and why, according to Menninger, the Secret Service “without explanation, stopped using the AR-15 immediately after Dallas.”

There might be room for reasonable doubt, but after reading the book years ago I became convinced that Donahue’s theory at least passes the preponderance of evidence (more likely than not) standard of proof. I’d bet on it.

The Brain's Need for a Story

When big things go wrong we often reject simple explanations. We don’t just want an answer; we want an explanation that fits the emotional weight of the event. We crave narratives with clear heroes and villains, sweeping complexities, and a sense of intentional design. We struggle to accept that life’s biggest disasters often come down to boredom-inducing factors like miscommunication, fatigue, or someone having a bad day. Or random physics.

At first glance, it’s somewhat astonishing that Menninger’s book didn’t make waves when it hit stores in 1992. But it actually makes perfect sense: It’s much more reassuring to see ourselves as belonging to a world with meaningful, designed narratives. Otherwise we’re left to accept the existentially painful reality that the world’s most important person was probably killed by a one-in-a-billion accident. Because Donahue’s theory didn’t prove or disprove any Oswald conspiracies, it could be ignored.

Psychology and neuroscience have repeatedly demonstrated that:

The brain hates randomness. It actively seeks to impose structure and causality on events, even where none exists. This is why people see cause and effect in absurd and random statistical correlations, or why JFK’s assassination must have been the result of a massive organized conspiracy.

We default to black-and-white thinking under duress. Stress simultaneously kicks our amygdala into overdrive and impairs the prefrontal cortex, leading our mind to oversimplify. Our brains regress and see good guys and bad guys, not nuanced bureaucratic mishaps.

Complexity feels more adequate than simplicity. If an event is monumental, our brains assume the cause must be equally monumental. This is known as Proportionality Bias (Lagnado & Sloman, 2004). We have a hard time accepting that world-altering events can originate from the same mundane chaos that makes our phone fall into the single most hard-to-reach spot under the couch.

This is particularly relevant in coaching conversations.

It’s me. Hi. I’m the author it’s me: If you’re finding value in the newsletter, consider supporting my ability to arrogantly describe myself as a paid writer by becoming a paid subscriber.

C-Suite Conspiracies

I routinely coach leaders who are stuck in loops of over-attribution. They come to me with their versions of the Kennedy assassination, convinced that a senior leader is undermining them, that a hiring decision was a Machiavellian power play, or that an organizational shift was meticulously engineered to sideline them.

Sometimes they’re right! Power dynamics are real and corporate politics aren’t always innocent. But more often, the truth is disappointingly simple: The CFO isn’t out to get them; they were just focused on something else that day. The SVP’s atypically curt email reply wasn’t because they’re upset with you; they were just firing it off during a Zoom call. Your colleague’s comment during that meeting wasn’t a criticism. The peculiar timing of that announcement was just a coincidence, not divine providence.

These banal explanations don’t feel good, but they are, overwhelmingly, the ones that match reality. Most mishaps are underwhelming. Most people are far less cunning and far more fallible than we like to imagine. Hanlon’s Razor comes to mind: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

When we’re stressed and things feel personal we naturally lean toward explanations that feel worthy of the moment. Once we can accept that not everything is a grand narrative with us at the center, we gain clarity and can move forward with more agency.

Resisting the Need for a Bigger Story

In these acute moments, coaching is about creating an opportunity to pause, zoom out, and try on other perspectives. It often comes down just to listening empathically and presenting alternative hypotheses that help broaden the field of view. A coach — or any practiced, trusted listener — is hugely helpful in these moments.

But you can navigate this yourself, too! The next time you find yourself crafting an intricate theory about why something happened, pause. Ask yourself these four questions:

Am I rejecting the simple explanation because it’s too simple?

Would this explanation still hold if I assumed good intent?

If my best friend told me this story, what alternative explanations would I point out to them?

Am I demanding a more complex story because I need the event to mean something more?

If you can interrogate your own desire for narrative, you might see reality more clearly. Not every corporate misstep needs to become your own personal Grassy Knoll.

That's it for this edition - please reach out if I can be at all helpful.

Be compassionate and intentional.

This takes me back to the “Oh sh!t I shot Marvin” scene in Pulp Fiction.

Just as we tend to misattribute negative outcomes to Machiavellian calculus, we are quick to call genius the guy whose $5000 seed investment in Uber turned a gazillion X profit. He may simply have been approached during a week he was feeling particularly loaded because his bonus or tax refund had just hit his bank account. There are likely a few people who ended up at Nvidia in the last couple of years not because they were particularly ambitious, but simply because a well timed LinkedIn notification popped up while they were waiting in line for a chicken avocado wrap. I think it goes back to our religious roots. We’ve never been able to shake our desire for a puppet master no matter how secular we become.