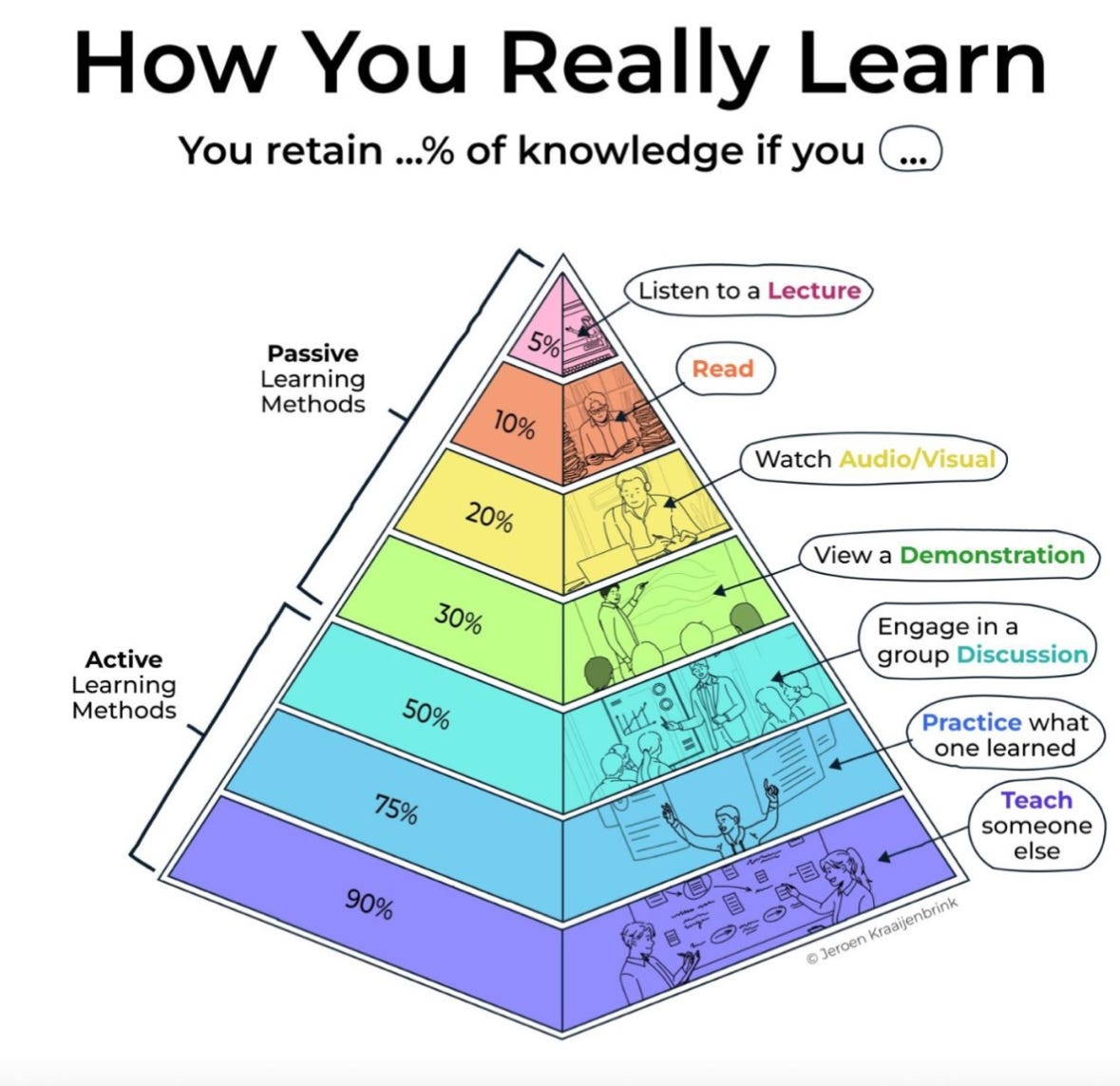

You’ve probably seen this image before. Maybe in a workshop, maybe in a PowerPoint from a well-meaning facilitator, or taped to a wall at a training session: The Learning Pyramid. It claims that we retain only 5% of what we hear in a lecture, but a whopping 90% if we teach someone else. And everything in between!

It validates our instinct that lectures are ineffective and active learning is better. But here’s the problem: None of this is grounded in actual research.

Where Did This Come From?

Despite being cited for decades, there's no credible evidence that this pyramid (sometimes called the ‘Cone of Learning’) was derived from empirical research. As far back as the 1970s, the National Training Laboratories (NTL) in Bethel, Maine, was credited with these figures. But when pressed, NTL reportedly admitted they couldn’t locate the original research.

Someone probably scribbled it down, it made its way into a presentation, and then took on a life of its own. The percentages are suspiciously tidy. There's no nuance. And there's no accounting for learner differences, content complexity, or context.

Learning researchers like Will Thalheimer and others have gone to great lengths to debunk this model.

The Learning Pyramid is educational clickbait.

Why We Need to Stop Using It

One might argue, “But the general idea still holds—experiential learning is better than passive learning.” Maybe. But simplifying complex instructional design into a set of fictitious numbers isn’t just misleading, it’s degrading.

Here’s why perpetuating this myth is actively harmful:

It undermines evidence-based practice. When myths like this dominate our workshops and training decks, they crowd out actual science. This leads to skepticism from participants, which undermines trust in the learning profession.

It misleads well-intentioned facilitators. The pyramid gives a false sense of certainty. It tells people there’s a universal “best” way to teach everything, ignoring the reality that effective learning depends on goals, context, and learner characteristics.

It stunts innovation. If we think the answer is always to “teach back” or “do more activities,” we might miss out on better solutions.

Pseudoscience is always problematic even when it points toward useful conclusions. Ditch the learning pyramid. After all, you read this and you’ll probably remember it pretty well.

That's it for this edition - please reach out if I can be at all helpful.

Be compassionate and intentional.