We’ve all seen a depiction of the Corporate Iceberg. You know the one I mean – where the manageable crest of ice floating atop the ocean belies the depth and breadth of the menacing structure below.

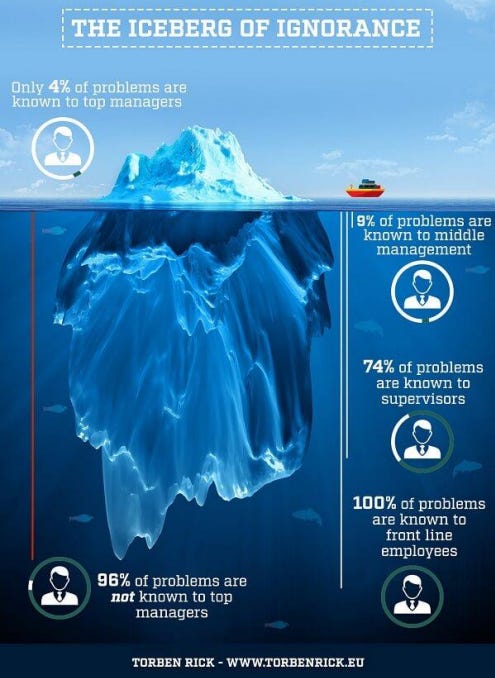

The “Iceberg of Ignorance” may well have been the first use of this what-lies-beneath framing. According to legend (yes, Legend. See below), back in 1989, a consultant named Sidney Yoshida studied problems at the automotive company Calsonic and found that executives were aware of only 4% of the problems known to frontline employees. Beyond just ignorance at the very top of the org chart, mid-level management knew of only 9% of what was known to frontline employees. Frontline supervisors were still only privy to three-quarters of issues. Thus, the Iceberg of Ignorance. What is seen by leaders floating at the top amounts to a nickel of the dollar’s worth of problems.

The study is referenced as a warning for all leaders: You don’t know just how much you don’t know. For every problem reaching your ears there are another 20 of which you are painfully unaware. A business school management course would offer the following takeaways from Yoshida’s work:

Importance of Communication and Traceability: Despite advancements in corporate communications since the 1980s, the fundamental issues in management highlighted by the study remain largely unchanged. The persistent gap in knowledge and understanding between different levels of an organization, especially between frontline workers and top management, underscores the need for more effective communication channels.

Two-Way Gap in Understanding: The Iceberg of Ignorance is not just about the lack of awareness among top executives; it also points to a gap in understanding in the opposite direction. The top-down management style commonly employed in many organizations often leaves frontline workers unaware of the broader challenges and decisions made by the company. This lack of understanding in both directions can be conceptualized as an "inverted Iceberg of Ignorance," highlighting a bilateral communication gap.

Impact on Engagement and Organizational Health: The differing perspectives within an organization can have significant consequences. Frontline employees who are not aware of the reasons behind their directives are often less engaged. Conversely, executives who are out of touch with frontline realities can miss critical issues related to quality and organizational culture, potentially leading to long-term damage to the company.

Iceberg or Loch Ness Monster?

What that management class probably would not have is verifiable data on the actual study conducted by Yoshida. If Yoshida even exists! Despite its mythical status, a thorough web search doesn’t produce any of the source material. Various works reference a talk called “Quality Improvement and TQC Management at Calsonic in Japan and Overseas”, apparently delivered by Yoshida at the 1989 International Quality Symposium in Mexico City.

But as some sharp online sleuths have discovered, there doesn’t seem to be any record whatsoever of such a talk, let alone such a symposium. This doesn’t mean that the information is fabricated. Intuitively, I have to imagine that such a conference existed, as does (did?) Yoshida. One would imagine that someone at Calsonic has a record of such work. But it is mysterious! Given its prevalence in management discourse, it is shocking to discover just how opaque its origins are.

That said, let’s assume it’s real.

Just 4%? So What?

Let’s assume every bit of detail is accurate and executives are only aware of 4% of the problems known to frontline workers.

Good. Yeah, that’s a good thing. Executives shouldn’t be aware of 100% of the problems known to frontline employees. For a few reasons:

Useful Insulation: The limited awareness of executives regarding frontline issues is not entirely negative. It serves as a form of organizational insulation. Frontline employees are often best positioned to handle the day-to-day challenges they face. Empowering them to address these issues without the constant oversight or intervention of executives fosters a sense of autonomy and responsibility. This empowerment not only enhances problem-solving at the ground level but also prevents the overburdening of executive bandwidth with minutiae. In essence, frontline workers solving their own problems, or at least having them addressed by immediate management, is a crucial aspect of efficient organizational functioning.

Focusing Executives: Consider the scenario where every issue known to frontline workers escalates to the top echelons of management. The result? A paralyzing inundation of problems, most of which are either too trivial or too context-specific for executive action. Executives would spend all day reacting to small tactical problems (many of you executives reading this are screaming “JAKE, I ALREADY SPEND ALL DAY DOING THAT!”). By ensuring that only the most significant issues – those that truly require top-level intervention and strategic decision-making – are escalated, organizations maintain a balance. Many of the 96% of problems should be tackled at the operational level, allowing executives to focus on broader strategic initiatives rather than being perpetually reactive.

Information Should Be Siloed: Not all information should be for everyone. The idea of keeping frontline employees somewhat insulated from the strategic complexities and broader challenges that executives grapple with has its merits too. It's not about withholding information for the sake of secrecy, but rather about ensuring that employees can focus on their immediate responsibilities without the distraction of high-level strategic concerns. This stratification of information helps maintain a clear operational focus at different levels of the organization.

4% Sounds About Right

I don’t know what the magic number of problems that reach the executive suite ought to be. And of course, it’s going to differ for a startup of 30 people and a multinational of 30,000. But I’m not convinced that 4% is inherently problematic. In fact, at a large organization, that may be way too high. The key is making sure that right problems reach executives – problems which only an executive can solve by the nature of their broader purview and access to other information rightfully unknown at lower levels.

That’s a good question for a frontline employee or manager to ask: Is this problem something that ought to be solved by someone with more strategic knowledge, or should I handle it?

My guess is that in today’s matrixed knowledge-work world, quite differently from that of an automotive company of the late 1980s, more frontline problems have interconnected features that rightfully do require slightly more strategic solutioneering. Fair enough. This highlights the importance of middle management in today’s world: Managers and Directors must tactfully forward what they learn from frontline employees to see if it warrants executive interference. Meanwhile, executives have to balance their desire to be informed and impactful with micromanagement. A slippery slope, to be sure.

In any case, we must reframe the inherent dangers of Yoshida’s iceberg. The problem is not executive ignorance writ large, the problem is that executives need to better provide an understanding of strategy and commander’s intent to equip frontline employees and managers with the authority and autonomy to solve problems themselves. Ignorance can be bliss, for everyone.